Human rights: universal, inalienable and indivisible

This blog is by Dr. Maria Ron Balsera, Research and Advocacy Coordinator for ActionAid International. She works on Tax Privatisation and the Right to Education: influencing education financing policy.

I’m writing this blog on the eve of Human Rights Day, following celebrations of the 30th anniversary of the Convention of the Rights of the Child.

On 10 December 1948 the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). This declaration was an effort to ensure that the abuses and atrocities against human dignity – such as those perpetrated by the Nazis – would never take place again. Human rights are universal, inherent to every individual without discrimination; inalienable, meaning that no one can take them away; indivisible and interrelated, with all rights having equal status and being necessary to protect human dignity.

Drafted at the onset of the Cold War, it was a fruitful historical compromise between the Western bloc, that pushed for civil and political rights – generally freedom from government interference such as freedom of religion, freedom from torture or equality before the law – and the Eastern bloc and countries under colonial rule - who championed economic, social and cultural rights. They are enabling rights that need the provision of services to be fulfilled, such as the right to an adequate standard of living, right to education or right to work. Human rights are based on the principles of equality, non-discrimination and dignity, transforming moral claims into rights to confront abuses and tyranny. ActionAid follows a rights-based approach supporting rights holders – individuals – to organise and claim their rights and to hold the duty bearers – state, government – to account. We analyse and confront power imbalances while supporting groups and individuals to fight poverty and social exclusion at local, national, regional and international levels.

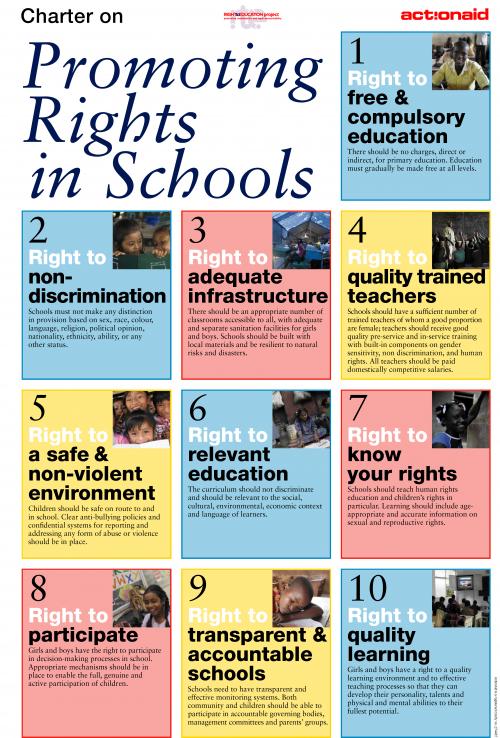

The Promoting Rights in School Framework is an innovative and participatory approach which focuses on strengthening public education following ten rights derived from international human rights law.

Over the past ten years this framework has been used across Africa and Asia, supporting the transformation of children and local communities into agents and leaders of change, which I’ve been able to witness in the project I coordinate. Education is a right and a multiplier of other rights. Broadly speaking and following not only the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, but also the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) – both binding instruments, unlike the Universal Declaration – the right to education requires that states:

- Provide free and compulsory education of good quality, at least at elementary stage, using the maximum available resources

- Respect the freedom of parents to choose and providers to establish alternative education institutions that meet human rights

- Protect individuals, particularly children, from violations of their rights (such as families, schools or private providers impairing or hindering the enjoyment of their rights).

Therefore, the state is the duty bearer and has the ultimate obligation to provide education. Private providers can offer a complementary or alternative option, as long as this complies with human rights, but they cannot supplant the role of the state – something which is happening in areas such as Accra or Lagos where private schools outnumber public ones. The state is also responsible for the adequate regulation of private education providers – which they largely fail to do. The Abidjan Principles, adopted in February this year, explain the human rights obligations of states to provide public education and to regulate private involvement in education. Its Article 25 refers to the obligation to prevent or redress direct or indirect discrimination in or through education, including systemic disparities in educational opportunities or outcomes, highlighting socio-economic disadvantage.

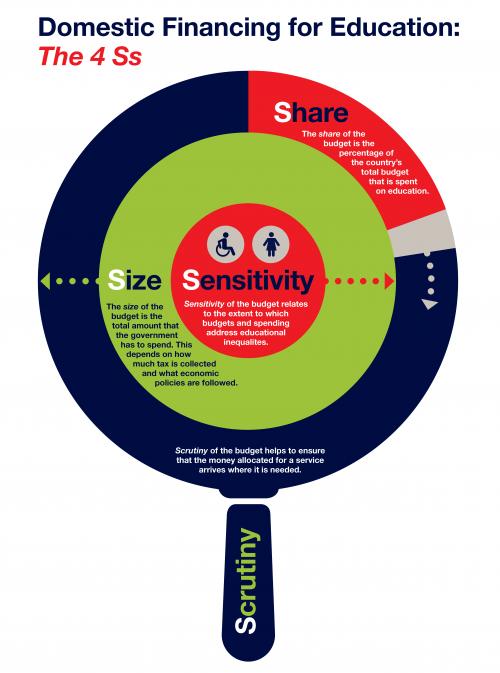

Our study in Ghana, Kenya and Uganda, which used the Abidjan Principles to understand the impact of privatisation on the right to education, concluded that these states are not meeting their obligations to provide free and quality education. This is partly due to the underfunding of the sector in these three countries, and the subsequent growth of the private sector. This growth is causing and entrenching social inequalities, leading to stratification and huge disparities of education opportunities. Ghana, Kenya and Uganda must fulfil their obligations to provide free public education of the highest attainable quality. Increasing the size, share, sensitivity and scrutiny of the budget is necessary to give the necessary resources to public schools and to adequately regulate private providers.

The right to education is a multiplier of other rights, enabling individuals to participate in society, to learn about healthy habits that can save their lives and the lives of those around them or to learn to live with others, enhancing the enjoyment of all other rights and freedoms (K Tomasevski, 2003). We need to ensure that education is available, there are enough schools, teachers and education resources at reasonable distance; accessible, free of social, cultural and physical barriers; acceptable, good quality education that enables every child to flourish; adaptable, child-centred and reflecting human diversity (K Tomasevski, 2003). Let’s celebrate Human Rights Day by holding governments to account to fulfil their obligations.